"Oppression has transformed Panahi’s art. Under the pressure of circumstances, he has turned from a classicist into a modernist, while at the same time transforming the very codes and tones of his frame-breaking aesthetic." - Richard Brody (The New Yorker, 2015)

Jafar Panahi

Director / Producer / Editor / Screenwriter / Actor

(1960- ) Born July 11, Mianeh, Iran

21st Century's Top 100 Directors

(1960- ) Born July 11, Mianeh, Iran

21st Century's Top 100 Directors

Key Production Country: Iran

Key Genres: Drama, Childhood Drama, Psychological Drama, Culture & Society, Docudrama, Satire

Key Collaborators: Iraj Raminfar (Production Designer), Aida Mohammadkhani (Leading Actress), Abbas Kiarostami (Screenwriter), Amin Jafari (Cinematographer), Narges Delaram (Leading Character Actress)

Key Genres: Drama, Childhood Drama, Psychological Drama, Culture & Society, Docudrama, Satire

Key Collaborators: Iraj Raminfar (Production Designer), Aida Mohammadkhani (Leading Actress), Abbas Kiarostami (Screenwriter), Amin Jafari (Cinematographer), Narges Delaram (Leading Character Actress)

"After serving as Abbas Kiarostami's assistant director on Through the Olive Trees (1994), Jafar Panahi made two features of his own that further developed the narrative perfected in Kiarostami's Where is My Friend's House? (1987), in which a child embarks on an obstacle-laden quest. Both The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997) concerned the trials and tribulations of little girls in crowded Tehran streets; their stressful journeys, shot in 'real time', are thrillers that double as microcosmic portraits of the city." - Lloyd Hughes (The Rough Guide to Film, 2007)

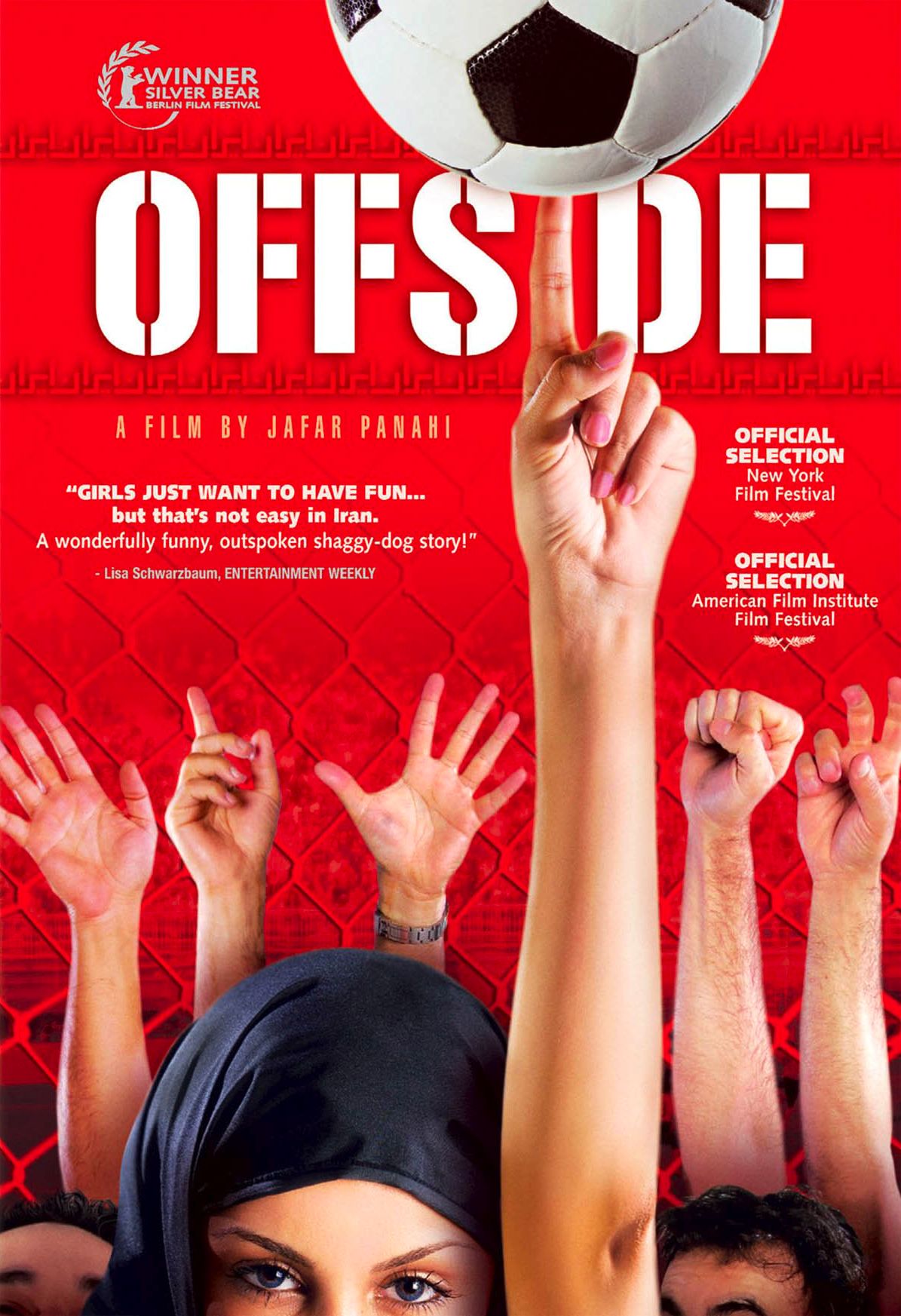

"Much loose talk is bandied around in the film world about directors’ bravery and the heroism of “guerrilla” film-making – but those terms genuinely mean something when applied to Iran’s Jafar Panahi. After making several robust realist dramas about the challenges of everyday life in his country – among them The Circle, Crimson Gold and the exuberantly angry football movie Offside – Panahi fell foul of the Iranian government, which threatened him with imprisonment, prevented him from travelling and banned him from making films for 20 years. He has protested by working under the wire to make three extraordinary works, contraband statements that are at once a cri de coeur from internal exile, and a bring-it-on raised fist of defiance." - Jonathan Romney (The Guardian, 2015)

Crimson Gold (2003)

"In his own rather startling way, Panahi’s films redefine the humanitarian themes of contemporary Iranian cinema, firstly, by treating the problems of women in modern Iran, and secondly, by depicting human characters as “non-specific persons” – more like figures who nevertheless remain full-blooded characters, holding on to the viewer’s attention and gripping the senses. Like the best Iranian directors who have won acclaim on the world stage, Panahi evokes humanitarianism in an unsentimental, realistic fashion, without necessarily overriding political and social messages. In essence, this has come to define the particular aesthetic of Iranian cinema. So powerful is this sensibility that we seem to have no other mode of looking at Iranian cinema other than to equate it with a universal concept of humanitarianism." - Stephen Teo (Senses of Cinema, 2001)

"Every new movie by Jafar Panahi is a miniature coup, an act of fearless political defiance. Banned from filmmaking by the Iranian authorities, who have kept him under house arrest for the last five years, Panahi risks his freedom, maybe even his life, each time he picks up a camera—which is surprisingly often for a man who’s been forbidden by law to do so." - A.A. Dowd (A.V. Club, 2015)

"Jafar Panahi, alongside his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, is considered as one of the most remarkable figures of the second wave of Iranian new wave cinema. In 2015, he was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival, the prize awarded to the best film at the festival. Panahi’s films realistically depict humanity and its struggles in Iranian society. He audaciously comments on political and social issues to challenge the authorities. Although he is one of the most suppressed filmmakers in Iran, he artistically changes limitations into art." - Azadeh Nafissi (The Culture Trip, 2016)

"With his frequent use of non-professional actors, real locations and episodic narratives, Panahi’s films betray the influence of postwar Italian cinema. Some of his later films earned comparisons to Bresson and Scorsese with their terse depictions of alienated protagonists who suffer for their exclusion from the mainstream, which seems to be both imposed and willed. Despite these echoes from the canon of European and American cinema, Panahi has clearly earned his place at the center of contemporary Iranian filmmaking, even though the country’s censors have banned most of his films. Besides his focus on children, Panahi’s approach to narrative reveals him to be a true disciple of Kiarostami: his films tell simple, compelling stories that exist primarily to create interactions among a number of vividly realized characters. Thus despite any number of memorable protagonists, Panahi’s films tend to become portraits of a community, a city, a neighborhood, a group of people." - David Pendleton (Harvard Film Archive, 2012)

"Not only is the documentary approach very helpful in terms of creating dialogue and improvisation, but it’s also very helpful when it comes to decoupage (the visual dynamic of the shooting script and of the editing). It almost forces you to be spontaneous. No matter how carefully you create a certain decoupage in your mind, you still have to make changes due to the abilities or lack of abilities of your actors. In a situation like this I think it’s an advantage if you edit your own films." - Jafar Panahi (BOMB magazine, 1996)

Selected Filmography

{{row.titlelong}}

GF Greatest Films ranking (★ Top 1000 ● Top 2500)

21C 21st Century ranking (☆ Top 1000)

T TSPDT R Jonathan Rosenbaum

21C 21st Century ranking (☆ Top 1000)

T TSPDT R Jonathan Rosenbaum

Jafar Panahi / Favourite Films

Bicycle Thieves (1948) Vittorio De Sica.

Source: Sodankylä Ikuisesti: Desert Island Films (1996)

Bicycle Thieves (1948) Vittorio De Sica.

Source: Sodankylä Ikuisesti: Desert Island Films (1996)

Jafar Panahi / Fan Club

Jonathan Rosenbaum, Richard Combs, Srijit Mukherji, Joachim Lafosse, Richard Brody, Kevin B. Lee, Adam Nayman, Robert Koehler, Peter Rist, A.O. Scott, Michael Atkinson, Godfrey Cheshire.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, Richard Combs, Srijit Mukherji, Joachim Lafosse, Richard Brody, Kevin B. Lee, Adam Nayman, Robert Koehler, Peter Rist, A.O. Scott, Michael Atkinson, Godfrey Cheshire.

"Fan Club"

These film critics/filmmakers have, on multiple occasions, selected this director’s work within film ballots/lists that they have submitted.

These film critics/filmmakers have, on multiple occasions, selected this director’s work within film ballots/lists that they have submitted.